Return to Treatments Available page

Balloon Angioplasty/Stent Placement rapidly restores flow within narrowed arteries and bypass grafts. The down side of this procedure lies in the risk of renarrowing, termed restenosis, the impairment in endothelial function that follows balloon/stent trauma to the arterial wall, the small risk of a procedure related complication, and the uncertain risk of stent clot formation when Plavix anticoagulant therapy is stopped.

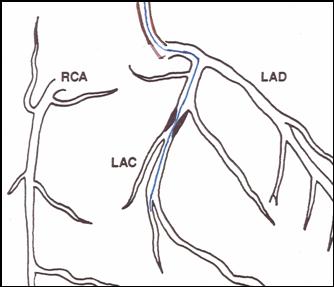

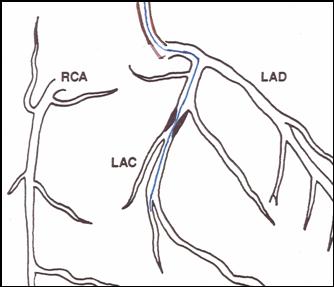

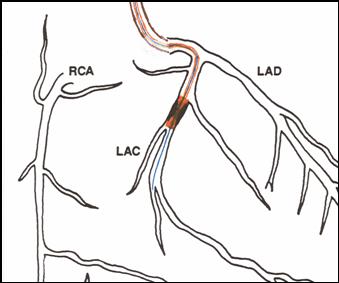

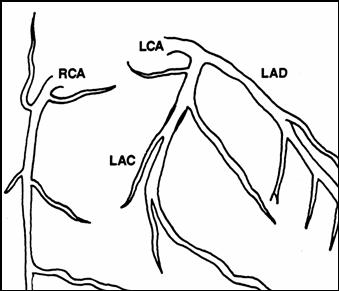

Basics of the Angioplasty Procedure - In diagnostic angiography, the coronary artery catheter is advanced into the proximal aspect, basically the entrance, of the left main or right coronary arteries. Contrast dye is hand injected and X-ray images are obtained, demonstrating the flow area within the artery and identifying points of narrowing (lesions). In percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) a flexible guidewire is snaked across the narrowing. A balloon tipped angioplasty catheter (with the balloon deflated) is then advanced over the wire and across the narrowing. The balloon is then inflated, scrunching the plaque down and into the vessel wall. The hardware is pulled out and you are left with a wide open or only minimally narrowed vessel. Your recovery time is short; you might be sent home later that day. The next day you could be back of the golf course.

Coronary Stenting - The problem with standard balloon angioplasty is "restenosis", a renarrowing of the vessel within the first 6 months post-procedure. The post-angioplasty restenosis risk is somewhere between 30 and 50%, depending on the type of narrowing being dilated and patient-specific factors (if your Lp(a) is elevated you are at greatly increased risk for restenosis). A stent is a flexible metal, collapsible sleeve that can be advanced over a guide wire into the just dilated vessel, then snapped open into place. The stent provides a rigid scaffolding within the just dilated vessel, and this maneuver decreases the restenosis risk for - stent placement is an important technical advance.

Brachytherapy - Sometimes dilated/stented narrowings will renarrow. The restenotic narrowing can be re-balloon dilated, or cut out with an atherectomy (sort of a high precision rotorooter) device; then a new stent is placed within the old stent, creating a "stent sandwich". Another maneuver is to place radioactive material within the new stent, a maneuver called brachytherapy. The radioactivity inhibits ingrowth of smooth muscle cells into the inner layer of the arterial wall, decreasing the risk of further restenosis.

Drug Eluting Stents - Widely hailed as "the breakthrough", these stents are soaked in drugs that slowly seep into, or "elute" into the just dilated artery, blocking the migration of smooth muscle cells into the inner wall and flow area, similar to the effect of brachytherapy. Restenosis is less frequent following placement of a drug eluting stent as compared to when a standard stent (now known as a "bare metal stent") is used.

Problems with Angioplasty/Stent Placement:

A. Acute procedure related complications - In diagnostic angiography, we pass the smallest catheter possible into your arterial system, take our pictures, and then get out of your body; risk here is low. PCI, in contrast, involves controlled trauma to the arterial wall, and larger catheter systems. In the early days of angioplasty, it was not uncommon for the artery being dilated to suddenly close off. A heart surgeon and operating room were always on standby, such that if the vessel closed, bypass surgery could be carried out within 30-60 minutes. These days, with the technology available, acute vessel closure just doesn't occur. Cardiologists are carrying out low risk angioplasty procedures in hospitals that do not provide open heart surgery. The major procedure related risk associated with PCI today involves bleeding or clotting at the arterial puncture site, as the PCI catheters are considerable larger than the devices we use in diagnostic angiography.

B. Endothelial Dysfunction - Balloon angioplasty wipes out the

endothelial cells that line the artery wall. Without endothelial cells,

the artery cannot make nitric oxide; it cannot vasodilate normally or resist

platelet mediated clotting. For this reason you might not feel back to

normal for several days following balloon angioplasty, and it is important that

you take aspirin and Plavix, at least for the short term. Of interest,

restenosis is basically due to endothelial dysfunction, a condition created by

the very act of dilating the vessel. Fortunately, the endothelium recovers

from the controlled trauma of balloon angioplasty fairly rapidly - not so

following brachytherapy and very much not so following placement of a drug

eluting stent. We can measure endothelial function, such as the ability of

an artery to dilate in response to a physiologic stimulus, say increased flow

due to arm exercise. The graphic below on the left shows that endothelial

function, the ability of the artery to generate nitric oxide, dilate, and resist

platelet mediated clot formation in impaired only briefly following balloon

dilation. On the right you can see what happens following brachytherapy

(and a similar phenomena occurs with drug eluting stents). The reference,

or non-instrumented artery dilated normally; we would expect this. The

stented

region

region does not dilate. It can't - it is tethered in metal; but this

doesn't matter as the artery is propped open so flow will be preserved.

Notice that the regions of the dilated artery proximal and distal to the stented

region dilate fairly well, but not normally in response to increased flow, that

is when a bare metal stent is placed. Following brachytherapy, however,

endothelial function within the entire artery is shot, and it stays that way for

a period of time. When we do see restenosis in a patient late post-stent

placement, it is typically not within the stent itself, but at its lip, at the

junction between the non-stented and stented region. Here the endothelium

is shot, but there is no metal sleeve to keep the vessel open. A new stent

can be placed across this region, but you can see the problem that we are

getting into with this technology. It appears that the endothelium may

never fully heal in a vessel treated with a drug eluting stent. The

standard recommendation is that you remain on Plavix for 3-6 months following

placement of a drug eluting stent. Stopping Plavix within this time frame

is suicidal. We have all had patients who decided to stop their Plavix (or

who could not afford Plavix but we forgot to ask them if they could afford a

$3/day drug), who suddenly clotted off their stents and experienced large, full

thickness heart attacks - a total disaster. To complicate matters, reports

are coming out now describing acute stent clotting following discontinuation of

Plavix, a full year out from drug eluting stent placement. At this time,

we really don't know when it is absolutely safe to stop taking Plavix. If

you can afford the drug, it might be best to simply stay on it until we know

more. Of course, this exposes you to a bleeding risk, actually a small

risk with Plavix alone, and a more significant risk (although not everyone

agrees on this) associated with the use of Plavix and aspirin together. If

you need a surgical procedure soon after placement of a drug eluting stent -

well forget it, you can't have it. If you go off the Plavix you could clot

off and die. This reality certainly complicates decision making in

patients who have many different problems, and who might be at risk of GI or GU

tract bleeding or who might need non-cardiac surgery. Here we might choose

a bare metal stent over a drug eluting stent, trading a slightly increased risk

of restenosis for a much lower risk of stent clotting should Plavix be stopped.

On a more sobering note, recently presented studies comparing 1, 2, and 3 year

outcomes in patients receiving standard bare metal vs. drug eluting stents

actually seem to favor the bare metal stents. In the words of one

authority, the use of the newer, drug eluting stents over the older, bare metal

devices "trades an reduced risk of restenosis, a typically slow to develop

problem that can be addressed medically or with repeat intervention, for an

increased risk of stent clotting formation, a rapidly developing, more difficult

to treat, life threatening disaster". Right now the jury is out on which

approach is best. Everyone in the cardiovascular medical community is

worrying over this issue, and more knowledge will be available in the near

future. My preference, as you are all by now aware, is to prevent the

artery from blocking off in the first place, but often this is not possible so

we hope that stent technology continues to advance and improve.

region

region does not dilate. It can't - it is tethered in metal; but this

doesn't matter as the artery is propped open so flow will be preserved.

Notice that the regions of the dilated artery proximal and distal to the stented

region dilate fairly well, but not normally in response to increased flow, that

is when a bare metal stent is placed. Following brachytherapy, however,

endothelial function within the entire artery is shot, and it stays that way for

a period of time. When we do see restenosis in a patient late post-stent

placement, it is typically not within the stent itself, but at its lip, at the

junction between the non-stented and stented region. Here the endothelium

is shot, but there is no metal sleeve to keep the vessel open. A new stent

can be placed across this region, but you can see the problem that we are

getting into with this technology. It appears that the endothelium may

never fully heal in a vessel treated with a drug eluting stent. The

standard recommendation is that you remain on Plavix for 3-6 months following

placement of a drug eluting stent. Stopping Plavix within this time frame

is suicidal. We have all had patients who decided to stop their Plavix (or

who could not afford Plavix but we forgot to ask them if they could afford a

$3/day drug), who suddenly clotted off their stents and experienced large, full

thickness heart attacks - a total disaster. To complicate matters, reports

are coming out now describing acute stent clotting following discontinuation of

Plavix, a full year out from drug eluting stent placement. At this time,

we really don't know when it is absolutely safe to stop taking Plavix. If

you can afford the drug, it might be best to simply stay on it until we know

more. Of course, this exposes you to a bleeding risk, actually a small

risk with Plavix alone, and a more significant risk (although not everyone

agrees on this) associated with the use of Plavix and aspirin together. If

you need a surgical procedure soon after placement of a drug eluting stent -

well forget it, you can't have it. If you go off the Plavix you could clot

off and die. This reality certainly complicates decision making in

patients who have many different problems, and who might be at risk of GI or GU

tract bleeding or who might need non-cardiac surgery. Here we might choose

a bare metal stent over a drug eluting stent, trading a slightly increased risk

of restenosis for a much lower risk of stent clotting should Plavix be stopped.

On a more sobering note, recently presented studies comparing 1, 2, and 3 year

outcomes in patients receiving standard bare metal vs. drug eluting stents

actually seem to favor the bare metal stents. In the words of one

authority, the use of the newer, drug eluting stents over the older, bare metal

devices "trades an reduced risk of restenosis, a typically slow to develop

problem that can be addressed medically or with repeat intervention, for an

increased risk of stent clotting formation, a rapidly developing, more difficult

to treat, life threatening disaster". Right now the jury is out on which

approach is best. Everyone in the cardiovascular medical community is

worrying over this issue, and more knowledge will be available in the near

future. My preference, as you are all by now aware, is to prevent the

artery from blocking off in the first place, but often this is not possible so

we hope that stent technology continues to advance and improve.

James C. Roberts MD FACC

12/07/06